Yesterday was just one of those days. First day back from holiday. Excited. Refreshed. Looking for stimulation. But with two challenging situations. Partly because each (IMHO) required different strategies for leadership.

Scenario one was primarily a request for direction regarding team function and internal practice.

Scenario two was a discussion about a piece of client work.

Followers of this journal may have read a recent post, “A team full of leaders or a team full of leading”. Our client base consists of lawyers, engineers, marketeers, consultants. Getting the best from such bright, motivated people is important. To some extent we use our own team as the test bed for the content of our workshops. I guess I also feel obligated to practice what I preach. So how did I lead in each of these scenarios?

The Value of Ambiguity

In scenario one, two of my colleagues wanted a decision made. It wasn’t a clear-cut decision and there was plenty of ambiguity (we don’t have a lot of rules here). My internal monologue was asking my colleagues, “Do you want me to tell you what to do?” That would have been massively the easiest thing to do.

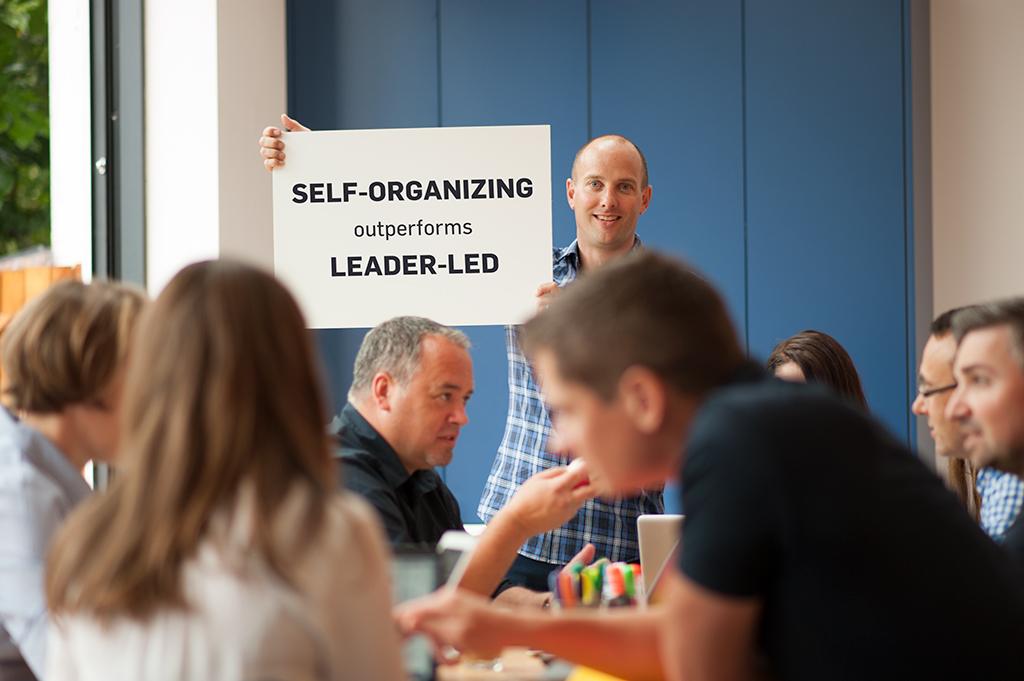

We have built our business on a hypothesis that, where possible, “self-organizing” teams outperform “leader-led” teams. This is at the core of agile leadership. Everyone in our business is empowered to lead projects. But sometimes it is not clear exactly who is making the decisions or who is responsible. So my strategy in this interaction: let them work it out.

This is a situation I’m pretty happy with. Ambiguity demands each of us to think about the best thing to do. Ambiguity promotes critical thinking and principle-centered decision-making. But ambiguity is a hard master, demanding constant attention. Ambiguity does not allow us to relax into rules. It constantly agitates us. Sometimes it means my job is to abdicate, disappear and decline.

Intrusive Leadership

In scenario two, four of us were debating the optimum strategy for a client project. The IW crew is a highly intelligent community that is good at intellectual debate. This ten-minute discussion went on for two hours, spanning both a meeting room and, when we got booted out of there, the kitchen. The crux of our debate was this: To what extent to do we want to get into conflict with the client. This can be one of the trickiest aspects of consulting.

The debate raised a moral dilemma. The client asks for X, to achieve Y. But will X actually work? And will it achieve Y? What would you do? We can’t ignore that money is a factor here. We could get paid to make X. We could make profit from making X. But what if we do it believing that X may not work, and that it won’t achieve Y?

In this case, intrusive leadership was required. Forcing a debate. Forcing tough conversation and difficult questions. Yet, where possible, still not directing leadership. I wanted to lead my team to clarity; I didn’t want to tell them what to do. This kind of leadership is more akin to academic debate or philosophical questioning. Jointly we came to some pretty cool strategies to work with the client to take the project to the next step. I think we were all happy with the outcome.

The Analogy

In chess, one way to win is to offer your opponent bait. Sacrificing a piece, say your queen’s pawn, that, when taken, sets in motion a chain of events and ultimately leads to your victory. The counter strategy by players who spot and resist the bait would be known as “queen’s pawn declined”.

Often, we can decline requests for leadership as part of a clear strategy. It may involve some “short term pain for long term gain”. But, if we want a team full of leading, it’s a strategy we will want to master.

Often, we can decline requests for leadership as part of a clear strategy. It may involve some “short term pain for long term gain”. But, if we want a team full of leading, it’s a strategy we will want to master.

The Tips

Here are some tactics from yesterday:

- Resist the temptation to start directing when facilitating will still work.

- Decline, where possible, requests to tell people what to do.

- Overcome our inner conflict aversion and speak up on matters of quality, safety and ethics.

- Resist pressure to do things for profits rather than principles.

- Decline attempts by the team to get a decision, leaving them to decide jointly.

This style of leadership is not an easy path. It’s a daily choice.