Before heading to dinner with my colleagues recently, Jonna (a self-professed extrovert) joked that he was ‘fearful for the lack of extroverts at dinner’. Clearly insinuating that it would be a long night. Being one of the ‘introverts’, I was determined to make the evening SO FUN that he’d be eating his words for dinner. The joke continued throughout the evening, with four introverts battling stereotypical one-liners with the sole extrovert:

- ‘Introverts are no fun’

- ‘Extroverts are loud and annoying’

- ‘Introverts can’t hold up a conversation’, etc, etc

… all things that clearly aren’t true in our cases.

At the end of the evening we were all far too full of great food and conversation for deep reflection, but the next day I got to thinking: Do these classic labels actually mean anything anymore?

Living under a label

I’ve always bought into introvert and extrovert labels. When I first moved to London I was fully ‘extrovert’. As a naive graduate, I thought that being extroverted was the right thing to do. I spoke to anyone and everyone, networked, embraced change, put myself in the centre of attention. The Guardian said ‘extroverted workers are 25% more likely to land a top job’, so I was going to be one of those people.

Four years later, after a quarter-life crisis and period of self-reflection, I became an introvert. I created more alone time, listened to other people’s opinions and took time to figure out if changes were right for me. I read more, I learned more about myself, and I quite frankly accomplished more goals. THIS is the way to be successful in life, I thought. I’ll be introvert from now on.

Two more years later and a bundle of life-stuff in-between, I’ve now found myself jumping between the two labels on a daily basis. Popular belief is that I still manifest as an introvert most of the time, but I can tick boxes for both camps very easily:

Introvert – Builds energy from alone time; prefers one-to-one conversations and fewer, more meaningful relationships? Tick.

Extrovert – Prefers to speak than listen; can be easily distracted; loves attention; speaks up when they have an opinion? Tick.

…Does that mean I’m now both?

Where’s the limit?

In life, and more-so the field of psychology, it’s standard practice to list people under stereotypical labels. On the face of it, these labels can be really useful. Using them can help you to predict how people will react in situations and to adapt yourself to fit in response. But in fact, labels are extremely limiting. They quieten the possibility that people are individuals with fluid thought processes and capacity to change.

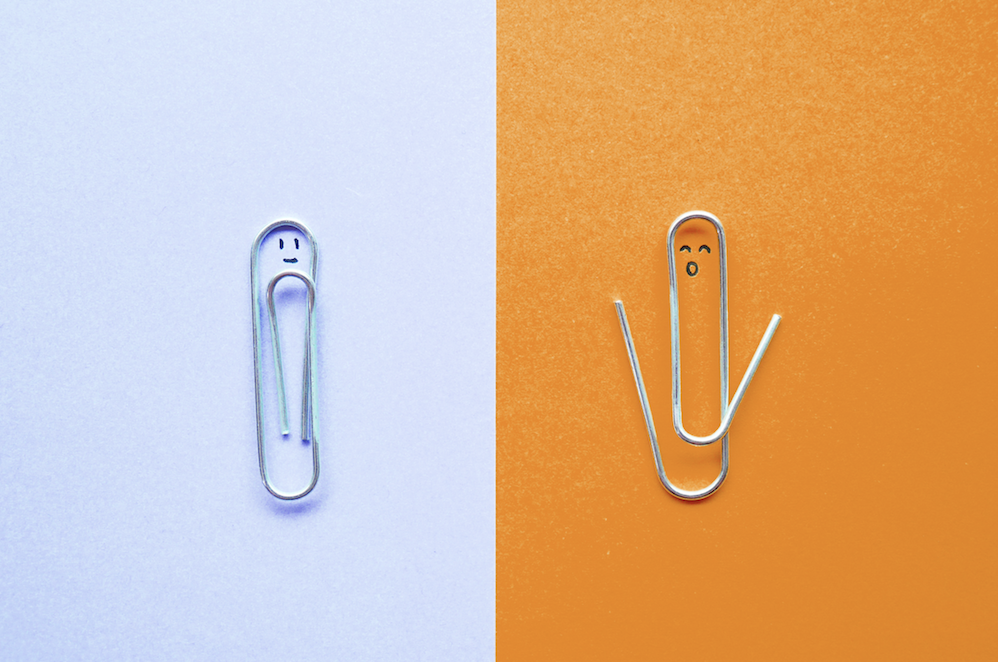

Carl Jung’s 1920s theory sets extroversion and introversion on a continuum, but in practice they are used as binary terms. You’re either one or the other. If you’re introvert, you’re no fun. If you’re extrovert, you’re loud and annoying. This is labelling in its simplest form. It pits two groups against one another and limits the potential of everyone.

Living without labels

For me, this doesn’t seem like a very rewarding way to live life. So instead, contrary to common practice and to Jung, I’m trialling extroversion and introversion as a scale on which individuals are in constant flux. Some tend to stick around a small area of the scale, whereas others may venture over larger a range. But the point is that they move. They’re not stuck with a limiting label. They’re not one or the other. So far it’s allowing me to understand a bit more about others – their preferences, abilities and potential – but also about myself and my own potential.

Where will I be in another two-three years without these labels to guide me through life? The answer is TBC, but probably a lot further than I’ve come so far.